Loading...

Koho-an Temple

Koho-an Temple is a hidden gem in Kyoto. It is hidden because it rarely opens its door to the general public (only once in five years or so). It is a gem because its interior and garden design is regarded as the masterpiece of Kobori Enshu (小堀遠州), an architect, garden designer, and tea ceremony master (as well as being a samurai lord, or daimyo) in 17th-century Japan.

In December 2020, I had a rare opportunity to visit Koho-an Temple and attend a tea ceremony at its teahouse Bosen. I found the temple's garden fully integrated into the building that it surrounds, more than any other Japanese gardens I have ever seen.

Below I'll take you to a virtual visit to the temple, with pictures mostly collected throughout the web (taking photo wasn't allowed during my visit, except for the entrance garden). At the same time, I'll explain what I think is the intention behind the temple's design: simulating a sailing trip to see the full moon reflected on the water surface of Lake Biwa, the ocean-like massive lake in Enshu's hometown.

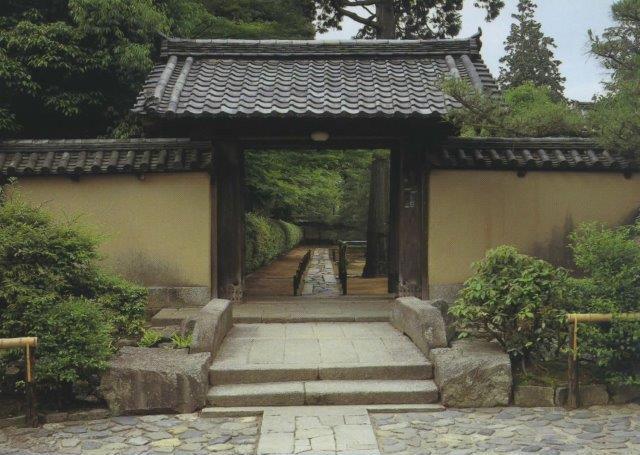

The Front Gate

The spatial experience of Koho-an Temple begins before you enter the temple. Approaching from the left side of the front gate, the first thing you notice is an empty moat along the wall:

Loading...

When you reach the front gate, you’ll walk over a stone bridge to enter the temple:

Loading...

Notice two things in the above photo. First, the stones on each side of the bridge are errected at an angle, rather than straight up. Second, the stone pavement beyond the gate does not form a straight line from the bridge: it slightly bends rightwards (as pointed out by Tanaka 2012, p. 126).

As far as I know, no one tries to understand why there is a moat along the walls of Koho-an Temple and why the composition of stones in the view of the entrance gate is made at an angle. I argue that the moat is meant to make the entire temple look like a structure built above the water along the shore. The angled arrangement of stones indicates that the above-water structure is riding on the wave.

Imagine you are visiting a habour. There is a building complex built on stilts above the water, with a floating wooden bridge connecting it to the shore. There is a gap between the shore and the floor of the building, through which you see the water beneath. The wave keeps changing the posistion of the bridge relative to the shore. The moat and the angled stone bridge may be intended to create such a scene in a visitor’s mind.

This interpretation might sound absurd to you. But it is not totally out of the context because the name of the temple, Koho (孤篷), means a solitary boat (Enshu Sado Soke 2020a).

Koho-an Temple was designed by Kobori Enshu, a 17th-century master of tea ceremony who also excelled at architecture and garden design—some people liken Enshu as Japan’s equivalent of Leonardo Da Vinci (Tanakadate 1996). As written in every guidebook on the temple (e.g., Kyoto Shunju 2020a), its design concept was a solitary boat floating on Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest lake near Enshu’s hometown to the east of Kyoto.

I think the entire site of Koho-an Temple represents a harbour where boats arrive and depart. If I see the temple this way, all of its design features will start making perfect sense to me. Keep on reading to see if it will make sense to you as well.

Entrance Garden

After passing through the front gate, you’ll find yourself walking on paving stones arranged to form a straight footpath (called nobedan in Japanese garden terminology):

Loading...

Stones of various shapes and textures are laid out with as narrow gaps as possible, to make a long rectangle. Imagine you yourself are asked to lay out these stones in this manner, and you’ll understand how laborious it must have been. When I saw this footpath, I was struck with awe.

As you walk, you’ll notice the long and narrow rectangular stones rhythmically arranged on both sides: left, right, left, right—as if they had responded to the movement of your feet. It made me want to walk further ahead.

If you look to your right while walking on the pavement, you’ll see the inner entrance of Koho-an Temple.

Loading...

When I visited the temple, I was asked to enter the building from here. For the true experience of visiting Koho-an Temple, however, you’re expected to walk further down the straight stone pavement.

Loading...

At the end of the path stands a pine tree in front of which the path turns to the right at a right angle:

Loading...

The structure behind the pine tree is soto-machiai (a roofed bench where the invited guests to a tea ceremony would take a rest until the host comes to greet them).

As pointed out by Vinfo (2012) and Yamaguchi (2012), the long, narrow stone at the top-left corner of the pavement gently curves to the right on the inner side, inviting your footsteps to the right. Did you ever imagine that a pavement can be considerate this much?

Just like the empty moat around the temple, no one discusses the design intention behind the long, straight stone pavement in the entrance garden. If the entire site of Koho-an Temple were a harbour on the shore of Lake Biwa, then I imagine this stone pavement would be a pier. The pier stretches straight and then extends further to the side at a right angle. The boat is not parked at the end of the straight stretch, but on the side of the pier or at the end of the right-angled side stretch.

At the very end of the right-angled side stretch, there is indeed the main entrance of Koho-an Temple that resembles the entrance of a houseboat.

Main Entrance

Loading...

According to the chief priest of Koho-an Temple, the roof of the main entrance is meant to be that of a houseboat of the time. The roof could have been more elaborate and magnificent to welcome guests, but that wouldn’t fit the design concept of the temple: a solitary boat floating on Lake Biwa. Houseboat roofs are simple with the straight edge of eaves. The design of the main entrance roof is faithful to it.

The simple shape, however, disguises how elaborate the roof design actually is. According to the chief priest, the roof is constructed with an unusual method called yoroi-buki (armour thatching). The roof is made of alternating layers of hiwada (the bark of Japanese cypress), used for the roofs of major shrines in Kyoto, and kokera(very thin, 2–3mm thick wood panels), employed for the roofs of temples such as Ginkaku-ji), to create a striped pattern that resembles the texture of samurai armours of the time.

Loading...

This striped pattern emphasizes the straight edge of the eave. It also corresponds to the straight line of the stone pavement you walked on to get here.

Main Hall Front Garden

When you pass through the main entrance, that is, when you board the “houseboat”, you’ll see a garden spread out on the left:

Loading...

And directly in front of you, the wide veranda of the main hall stretches straight out:

Loading...

It looks like the deck of a boat, don’t you think?

Take off your shoes and step up onto the veranda, and see the garden on your left again:

Loading...

This garden is very simple and purely geometric: linearly trimmed hedges and sandy soil. It is believed that this garden represents the waving surface of Lake Biwa (Uchida 2000, page 164, and Vinfo 2012). If the veranda were the deck of a boat, the hedge on the near side of the sandy ground, trimmed in a straight line, would be a wave caused by the boat moving forward. The two-tiered hedge on the far side of the sand would be the waves coming forward to lap against the boat. As you walk on the veranda looking at the garden, you can feel as if you were on a boat heading somewhere.

The above photo is not accurate colour-wise, by the way. The photo below is closer to the real view, taken from an angle looking back after walking along the veranda for a while:

Loading...

If you’re surprised by colour in the above photo, you’re a connoisseur of Japanese garden design: red clay is rarely used in historical gardens in Japan. According to the chief priest, red clay is characteristic of the area around Koho-an Temple. But doesn’t it contradict with the design concept, a solitary boat on Lake Biwa? How can red clay represent the water surface of a lake? In karesansui rock gardens, water surface is represented by the spread of gravels, not reddish sand.

Personally, red clay reminds me of a wilderness in North America. But that’s an association I’ve learned by watching TV. For the Japanese people in the 17th century, of course, this association cannot be the design intention.

I speculate that red clay is meant to represent the water surface of Lake Biwa tinted orange at sunset. Again, no one suggests this interpretation. But it will make sense later during your visit to Koho-an Temple. Bear with me for a moment.

One last thing about the Main Hall Front Garden: according to the chief priest, Funaoka-yama, a small hill in the neighborhood, was originally part of the garden view — a garden design technique known as the borrowed scenery. The shape of the hill would resemble a boat floating in the distance on Lake Biwa, according to the priest:

Loading...

In the latter half of the 20th century, high-rise buildings rose up between the temple and the hill. Tall trees have been planted around Koho-an Temple to keep modernity out of the 17th-century garden view. Today it is impossible to see the “boat floating in the distance”.

Many gardens with borrowed scenery in Kyoto have suffered from the same fate. With high population density typical of East Asia, it is not easy to preserve the historical landscape in Japan.

Teahouse Garden

At the rear end of the veranda is a staircase that leads to the garden on the other side of the Main Hall. While the guided tour during my visit continued inside the Main Hall, those guests invited to a tea ceremony would go down the stairs to the garden. If the Main Hall were a boat, you would get off the boat here, where you would see this view of the garden:

Loading...

According to the chief priest, the pebbles in the foreground are meant to resemble water surface. Stepping stones lead to the private garden representing the Eight Best Views of Lake Biwa (Oumi hakkei 近江八景).

But you as a guest to Koho-an Temple are supposed to turn right here, and you’ll see a straight line of stepping stones embedded in tataki, an earthen floor made of red clay, slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) and bittern (the leftover from extracting salt out of sea water, used to make tofu in Japan):

Loading...

At the end of the earthen floor stands chozu-bachi, a hand basin made of stone—typical of Japanese garden furniture. When you reach this point and turn to the right, you’ll find the entrance to the teahouse, where a tea ceremony is going to take place.

Laid out on the left of the footpath are the pebbles to represent water surface. They made me imagine fine water ripples across the surface of water.

Although not shown in the photo, the eaves of the roof extend over this earthen floor to keep it dry on rainy days.

One thing is very clear: the stepping stones and the hand basin will make visitors to expect that the entrance to a teahouse is just around the corner.

Both stepping stones and hand basins are commonly found in Japanese gardens. But they were originally invented as scenery to decorate the footpath to a teahouse during the late 16th century (Kozu 2009, Ch.4 Sec.4 and Ch.5 Sec.5). Koho-an Temple was built in the mid-17th century, when people must have had the idea that the stepping stones and the hand basin would signify the pathway to a teahouse.

As I’ll explain later, the entrance to a teahouse is the climax of the spatial experience of Koho-an Temple. At this point, therefore, it is necessary to make the guests well-prepared for the impending experience.

Now, what about the story of sailing across Lake Biwa that Koho-an Temple’s spatial design has told us so far? What does walking on the earthen floor signify in this context?

As far as I know, no one tries to interpret this earthen floor with embedded stepping stones. In other words, there is room for imagination to have fun. :-) I think there are two interpretations.

I. Sailing on a small boat

One interpretation is sailing on a smaller boat. A teahouse is typically a small hut. So it cannot be entered by a large boat of the scale of the Main Hall. In fact, as we’ll see below, the entrance to Koho-an Temple’s teahouse is structured in a similar way to a water entrance in which a boat can directly enter into the building.

However, if that were the case, it would be more appropriate to place the stepping stones in the midst of the pebbles that resemble the rippling surface of water, instead of making them embedded in the earthen floor.

II. Transferring to board a small boat

An alternative interpretation is that the earthen floor represents a pier to transfer to another boat called a teahouse. With this interpretation, the straight arrangement of stepping stones makes sense. Stepping stones usually represent a winding mountain path so that a teahouse in the middle of a city will turn into a hut deep in the mountain in a visitor’s mind. To represent a pier, therefore, a winding path of stepping stones would be inappropriate.

As far as I know, however, no one interprets the teahouse of Koho-an Temple as a boat. There is no interior design feature in the teahouse that evokes a ship.

I’ll revisit the question of which interpretation is more appropriate, once we sit down in the teahouse.

Now is the climax of the spatial experience of Koho-an Temple: entering the teahouse called Bosen (忘筌).

Teahouse Bosen

Unfortunately, there is no photo available for how the entrance to Bosen looks like when seen from the outside. Seen from inside the building, the entrance looks like this:

Loading...

The cylindrical hand basin in this photo is the one you saw at the end of the straight stepping stones. Therefore, when you reach the hand basin and turn to your right, you’ll see paper screens hanging from above with the lower half open, through which you can enter the teahouse.

Some people (e.g., Enshu Sado Soke 2020a) point out that this entrance resembles the water entrance hall where visitors get off their boat and directly land on the inside of a building. A real example is found in Hiun-kaku Pavilion at Nishi-Hongwanji Temple, also in Kyoto:

Loading...

It is indeed similar-looking. This is why walking on the straight stepping stones before entering Bosen may be interpreted as sailing on a small boat.

To appreciate the significance of this entrance, we need a bit of knowledge on the social background of 17th-century Japan and the tradition of tea ceremony.

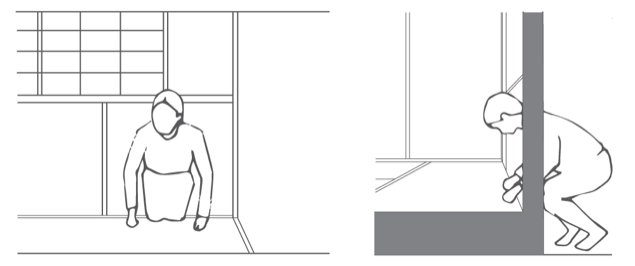

The gap under the paper screens is lower than one’s height. This is a big deal in the 17th-century feudal society of Japan, where those ranked higher than others would never bow his head. To enter Teahouse Bosen, even the most powerful samurai would have to bow his head.

Forcing guests to bow while entering a teahouse was not a new idea. It was the idea invented by Sen no Rikyu (千利休) with a teahouse entrance known as nijiri-guchi (躙口):

Loading...

It is an architectural device that makes everyone—noble and humble—equal inside the teahouse. A revolutionary idea of the time.

What makes Teahouse Bosen unique is the way it achieves the same idea, not with the use of nijiri-guchi but with the hanging paper screens. There is no other example of a teahouse entrance like this one.

When you bend your head, pass under the hanging paper screens and then look up, you’ll see a view of teahouse interior spread out:

Loading...

If you feel something weird with this view, you’re a connoisseur of Japanese architecture. Notice that the tie beams (the horizontal pieces of timber placed at the upper middle of pillars) are of the same height across the room, including tokonoma (床の間) on the right half of the back wall.

Tokonoma is an alcove with a tatami floor to display a hanging scroll (as shown in the above photo) and/or other ornamental items such as ikebana flower arrangement. For a typical Japanese room, the alcove’s tie beam is sightly higher up than the rest of the room:

Loading...

According to the chief priest, this special arrangement prevents the ceiling from looking too high when you bend your head to enter the room. In other words, this teahouse is not a place for the host to show off his dignity to the bowing guests, but a place to make them feel at ease.

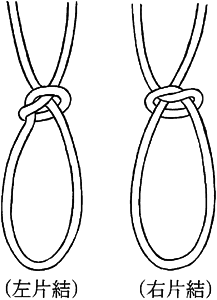

After entering the room, the guests turn around to face the entrance and purify their hands by scooping water from the hand basin. From the porch of the teahouse, the hand basin looks like this:

Loading...

The inscribed Chinese characters read tsuyu-musubi, meaning a form of knots that resemble the ear of a rabbit:

Loading...

Why rabbit ears? It refers to the rabbits that appear in a passage from an ancient Chinese philosophy book called Zhuangzi, from which the name of the teahouse — Bosen (忘筌) — is also derived (see the end of the first line):

筌者所以在魚、得魚而忘筌。

蹄者所以在兔、得兔而忘蹄。

“A fish trap exists to catch fish; thus, once you catch fish, forget about the trap. A rabbit trap exists to catch rabbits; thus, once you catch rabbits, forget about the trap.”

The passage reminds us of the importance of remembering the purpose (catching fish or rabbits), not the means to achieve it (the trap).

Some people (e.g., Kyotofukoh 2006) suggests that the shape of the tsuyu-musubi hand basin resembles a mortar used to make mochi (rice cakes). Since ancient times the Japanese people have likened the shape of lunar craters to a rabbit making mochi:

Loading...

In case you have no idea how mochi is traditionally made in Japan:

Loading...

If you carefully watch the full moon rising to the southern sky, you'll notice that the moon slowly rotates clockwise. I imagine ancient Japanese people would liken the rotation of the moon surface to a rabbit hammering down the pestle onto the mortar.

Just a single stone hand basin sparks a variety of cultural knowledge into our mind. It is a piece of art.

Now back to the garden. Once the guests are seated on the tatami floor of the teahouse (remember: Japanese people would historically take seats on the floor inside a house) and look at the direction they came from, they will see this view:

Loading...

Water surface, represented by the pebbles, and the land beyond, represented by the greenery, are seen through the “water entrance hall”. The stone lantern may be meant to be a lighthouse visible offshore.

The sky is invisible from this teahouse. It reminds me of how Japanese aristocrats during the Heian period (794–1192) would have admired the full moon: they wouldn’t look up to see the moon directly but look down on its reflection on the surface of a pond (Wakamura 2012). Enshu, the designer of Koho-an Temple, is known to be a fan of the Japanese aristocratic culture, such as waka poetry (Enshu Sado Soke 2020b).

As I'm thinking about it, the top of the hand basin suddenly looks to me like the moon reflected on the water surface:

Loading...

As mentioned above, the hand basin is associated with rabbits making rice cakes on the moon. Also, if the red soil in the Main Hall Front Garden were Lake Biwa dyed orange at sunset, then by the time you arrived at this teahouse, the sun would have set with the full moon rising in the sky.

Every dot is connected now.

It may be only me who interprets Koho-an Temple this way. But the reflection of light on water surface that reaches inside the teahouse was indeed the design intention of Enshu. Take another look at the ceiling:

Loading...

The wood grain of cedar is vividly highlighted on the ceiling. According to the chief priest, the grain is meant to be the reflection of light from the rippling surface of the water represented by the pebbles in the teahouse garden.

If you’ve never seen the reflection of water ripples on the ceiling, here is a real example:

After seeing all these, it now seems a bit unreasonable to liken the entrance to the teahouse as the water entrance hall. The view through the water entrance hall cannot be this rich. It is also difficult to imagine that the reflected moonlight reaches the ceiling through the water entrance hall.

A more natural interpretation is that Teahouse Bosen is meant to be a small boat floating on Lake Biwa on a full moon night. The view seen from under the hanging paper screens may be the view seen under the eaves of the roof of a houseboat. A real example can be seen at a moon-viewing event held on the Mid-autumn Festival at Osawa Pond, a massive garden pond built in west Kyoto in 810:

Loading...

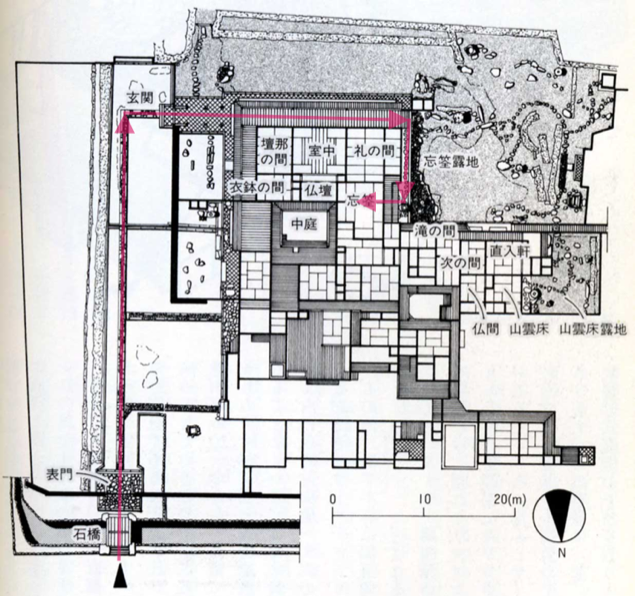

Plan of Koho-an Temple

To conclude the virtual tour of Kono-an Temple gardens, let me show you the plan of the temple, with the indication of how this article took you through the journey of experiencing the gardens of Koho-an Temple:

Loading...

We started our journey from the black triangle at the bottom left. We walked straight up from there, turned right at 90 degrees, walked straight facing rightwards, turned right again, walked straight downwards, turned right again to enter Teahouse Bosen (which is actually a room in the Koho-an Temple’s Main Hall).

I’m more than happy if you now feel like you’ve actually visited Koho-an Temple. :-)

Acknowledgement

I thank Kyoto Shunju Kotonari-juku for organizing the guided tour of Koho-an Temple and tea ceremony at Teahouse Bosen on 13 December, 2020, and the Chief Priest of Koho-an for explaining various details of the spatial design of Koho-an Temple.

This article is the English edition of my own article written in Japanese on 3 January, 2021.

References

Anonymous (2014) “Kobori Enshu ga konryu shita Daitoku-ji Tacchu Koho-an he” [Visiting Koho-an, the sub-temple of Daigoku-ji built by Kobori Enshu], Kodera to oshiro no tabi nikki II, Oct. 17, 2014.

ayayay0003 (2014) “Daitoku-ji Tacchu Koho-an” [Koho-an, the sub-temple of Daitoku-ji], Arisu no Trip, Oct. 14, 2014.

Enshu Sado Soke (2020a) “Kobori Enshu – kenchiku & sakutei” [Kobori Enshu — architecture and garden design], the website for Enshu Sado Soke.

⸻ (2020b) “Kobori Enshu – shoga & waka” [Kobori Enshu — calligraphy and Japanese poetry], the website for Enshu Sado Soke.

Japan Architecture (2021) “Nijiri-guchi”, Japan-architecture.org.

Kozu, Asao (2009) Chanoyu no rekisi [History of the tea ceremony]. Tokyo: Kadokawa.

Kyotofukoh (2006) “Koho-an Temple”, Kyotofukoh.jp.

Kyoto Shunju (2020a) “Daitoku-ji Koho-an”, Leaflet given to the visitors to Koho-an.

⸻ (2020b) “Daitoku-ji Koho-an tokubetsu haikan to juyo bunkazai ‘Bosen’ deno ochakai” [A special visit to Daitoku-ji Kohoan and a tea party at Bosen, an Important Cultural Property], the website for Kyoto Shunju Kotonari Juku.

Miura, Yasuko (2020) “Tsuki de usagi ga mochi-tsuki shiteiru nowa naze? Kaigai deno tsuki no moyo no mirare-kata” [Why is a rabbit making rice cakes on the moon? How people outside Japan see the craters on the moon], Allabout.co.jp.

Nakao, Katsuharu (2010) “Daitoku-ji Koho-an Bozen”, Futsu no Ie Futsu no Kurashi wo Motomete, Oct. 25, 2010.

Nishi-Hongwan-ji (2021) “Hiun-kaku”, the website for Nishi-Hongwan-ji Temple.

Shimoyama, Shinji (2019) “Daitoku-ji Koho-an”, Nihon no mokuzo kenchiku koho no tenkai [The evolution of wooden construction methods in Japan], Chap. 4, Sec. 2-3.

Shogakukan (2006) "Tsuyu-musubi" , Seisen-ban Nihon Kokugo Dai-jiten [Japanese language dictionary: concise edition], Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Tanaka, Shozo (2012) Sarai no “Nihon no niwa” kanzen gaido [The complete guide of “Japan's gardens” by Serai magazine]. Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Tanakadate, Tetsuhiko (1996) Kobori Enshu monogatari – nihon no Reonarudo Da Vinchi [The Story of Kobori Enshu — Japan’s equivalent of Leonardo Da Vinci]. Tokyo: Chobun-sha.

Uchida, Shigeru (2000) Interia to nihon-jin [Interior and the Japanese people]. Tokyo: Shobun-sha.

Usagi (2015) “Daitoku-ji Koho-an”, Usagi no Blog, Aug. 3, 2015.

Vinfo (2012) “Daitoku-ji Koho-an sono 4” [Daitoku-ji Koho-an Part 4], Haikai no Kioku, Aug. 11, 2012.

Wakamura, Ryo (2012) “Kangetsu gyoji” [Moon-viewing Events], Kyoto-tsu no Susume, August, 2012.

Yamaguchi, Sumio (2012) “Koho-an teien” [Koho-an Garden], Gekkan Kyoto Shiseki Sansaku Kai, Issue 63, Feb. 19, 2012.

Yoshikawa, Isao (1989) Stone Basins: The Accents of Japanese Gardens, Tokyo: Graphic-sha.